Education

Educational reform for the Victorian women’s movement chiefly concerned the provision of secondary and higher education for middle-class girls and young women. Elementary education for children of the working class had been taken in hand by the Church of England National Society, and its Nonconformist rival, the British and Foreign Schools Society. The expansion of their efforts, and the gradual involvement of the government, offered welcome career opportunities in teaching, particularly for daughters of the artisan class, but did nothing to address the wretched state of educational provision for girls in the middle class.

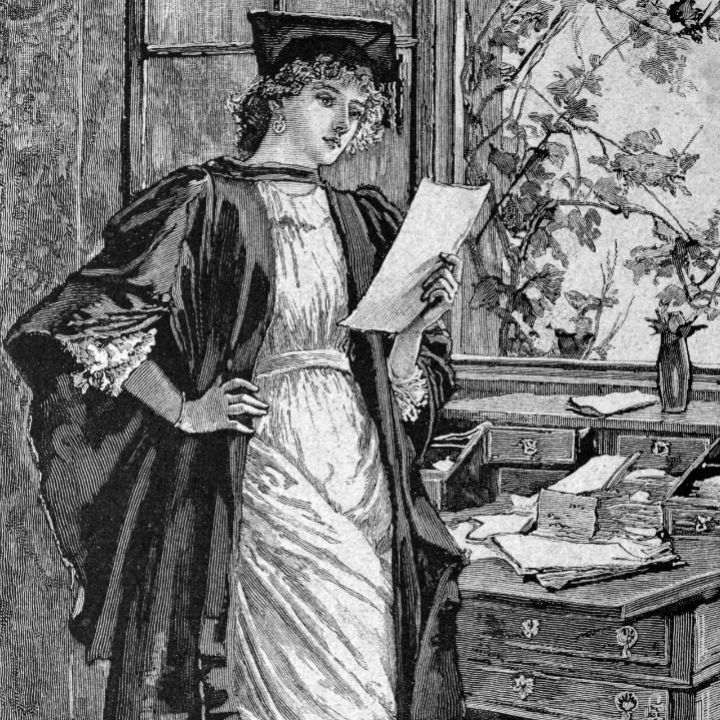

Here the options were severely limited: self-education at home, perhaps helped out by a college-educated brother; the services of a governess, unqualified and poorly paid; or attendance at a small boarding school, where the emphasis was on social accomplishments rather than academic attainments. Campaigns for reform were fuelled in part by the excess of women over men in the population, and the consequent need of increasing numbers of ‘surplus’ women to find employment compatible with their status as ladies, but the arguments most frequently advanced were moral rather than practical: properly educated women would make better wives and companions, wiser mothers, and more useful members of society.

Reform began with the foundation in 1848 of Queen’s College, set up to provide training for governesses, and of Bedford College a year later. Queen’s quickly established itself as a school, with pupils aged from nine years upwards; students from both Queen’s and Bedford went on to start schools of their own—among them, Cheltenham Ladies’ College, the North London Collegiate School, and those founded by the Girls’ Public day School Company—where the focus was on intellectual development. In 1864 the Schools Inquiry Commission found only 13 girls’ schools to investigate; by 1890 the number of endowed schools for girls had risen to eighty.

The improving level of secondary education, and the evidence, as the Schools Inquiry Commission put it, that it was not ‘natural causes’—that is, some innate female deficiency—but ‘want of due method and stimulus’ which had hitherto held women back, seemed to lead logically to the provision of higher education. In 1869 Emily Davies founded Girton College, with a mere five students, followed soon after by Newnham College at Cambridge and Somerville College and Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford. These advances were strongly resisted. In part the objections were clearly self-interested: the admission of women to study medicine, for example, threatened to diminish the standing of the profession. But there was also opposition from a number of men of science, on the grounds that women who undertook higher education would inevitably impair their reproductive systems, to the detriment in the long run not only of their own moral and physical health, but also that of the nation.

The only sufficient answer to such protests lay in the academic success and evident well-being of women students, and the argument was won over time. Even so, it was not until 1948 that women were admitted as full members of Cambridge University, and allowed to graduate with honours.

This section brings together the most significant documents on women’s education in the nineteenth century, including writing by such leading figures as Emily Davies, Lydia Becker, Barbara Bodichon and Frances Power Cobbe, selections of girls’ school stories, and memoirs and recollections from the first women to experience university life. It also includes some of the key studies of the debate about women’s education and its relation to ideologies of womanhood from, among others, Sara Delamont, Lorna Duffin and Carol Dyhouse.